|

The following information was taken from the NDSS website:

Quote, “Down syndrome regression disorder (DSRD), also referred to as regression, is a rare but serious disorder that occurs in some adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome. Regression is used to describe the loss of skills an individual has previously learned. These skills can be daily living, language, movement, or social skills. The loss is often sudden and occurs over a period of weeks to months. Since DSRD may be caused by a variety of factors, the first priority is to determine the most likely cause. Individuals who are younger than 10 years or older than 30 years are very rarely diagnosed with DSRD." To read the article click here. To download the checklist, scroll to the bottom of the page and click on NDSS Resources, and then click "Download the Down Syndrome Regression Checklist pdf here"

0 Comments

Written by Jill Hicks, Speech-Language Pathologist, November 2022 We all want our students with Down syndrome to succeed. Every goal we choose to work on will likely require lots of practice until it is learned and carried over. Given the intensive amount of practice required, there is necessarily a finite number of skills that can be practiced at any one time. Choosing the right goals therefore becomes extremely important. What we choose to work on will directly impact the student’s ability in that area. It is well known that speech and language are an area of particular weakness for most people with Down syndrome. We also know how important verbal communication is in numerous areas of life. Being able to speak well enough to be understood impacts social connection, academic performance, employment opportunities, independence, and ultimately quality of life.

This challenges us to step back and assess our goals in light of our student becoming an adult. It is easy to choose goals based on what content is being taught at a particular grade level, and we all naturally gravitate to goals that allow us to use skills we have, and programs we’re familiar with. However, we need to look beyond what is familiar and comfortable, and instead focus on the student’s needs, setting goals that lead to successful adulthood. Clear verbal communication is a basic academic skill. It is addressed in curriculum guidelines as shown in the Nova Scotia government’s document English Language Arts Primary Guide available online.

These outcomes require a foundational level of oral language ability for communication. And communication is successful when the oral communication is intelligible enough to be understood by the listener. So a child with poor or reduced intelligibility will have difficulty meeting even the entry level of academic skills in language arts. This highlights that speech is a fundamental skill. For a child in a grade higher than Primary (kindergarten), these fundamental oral language goals are still very much applicable. For many children with Down syndrome who have poor speech intelligibility, improving speech intelligibility should be their primary academic goal. Knowing this should help us as SLPs and educators put a primary and weighty focus on developing the student’s speech. This focus is reflected in a careful assessment of the child’s speech and language, setting specific articulation goals, and allotting significant time every day to practice speech skills.

As we make speech development our highest priority and allot time for intensive daily practice, we give the student the highest likelihood of achieving intelligible speech. We prepare the student for an adulthood with successful relationships, work and independence.

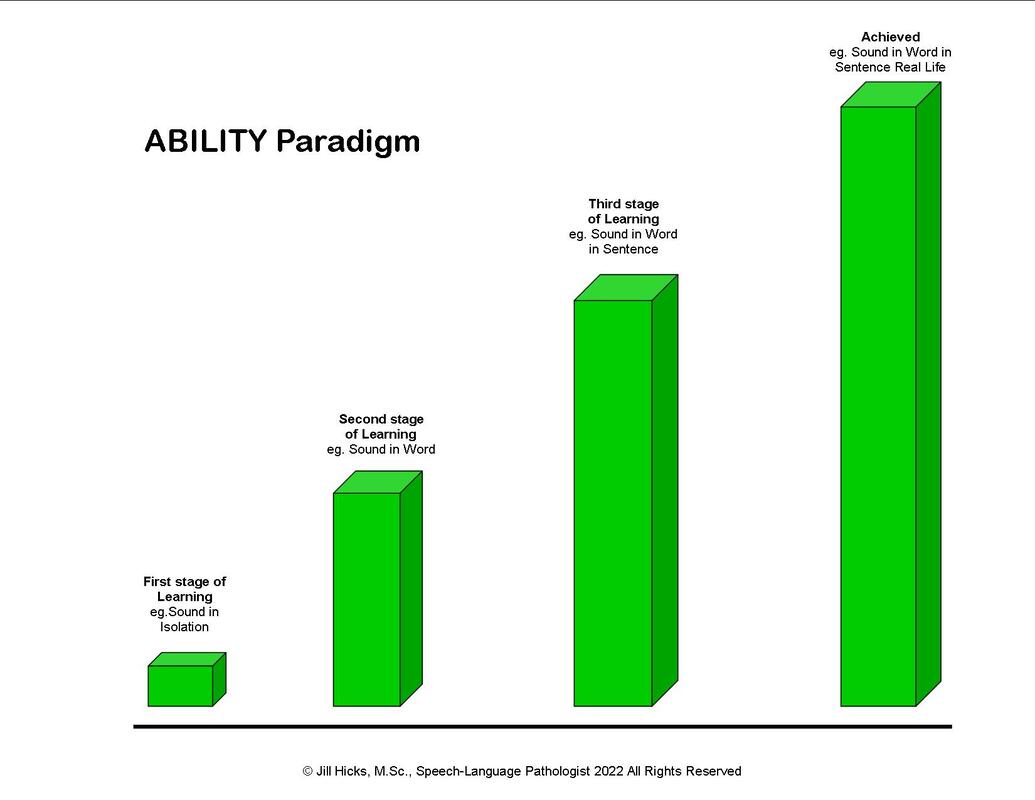

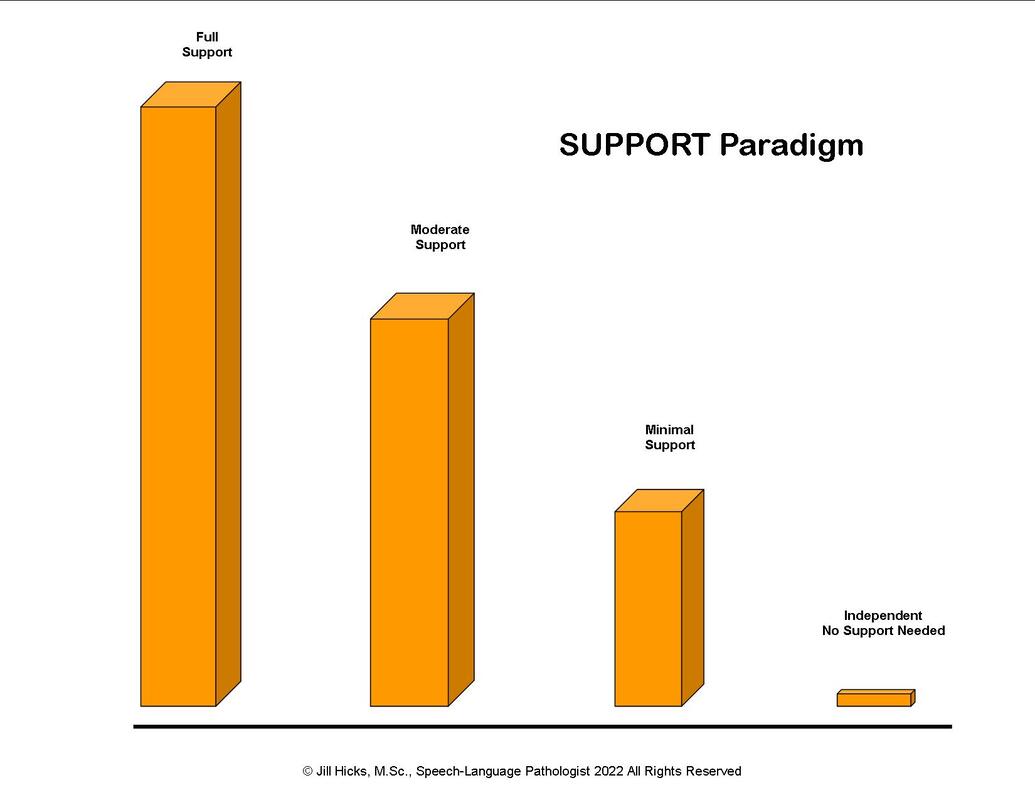

How providing the right amount of support enhances skill development. Written by Jill Hicks, November 2022As parents and professionals working with children with Down syndrome, we want to help them succeed. In this blog post I’m going to address the reciprocal dance between skill development and support. I like to think of skills and support as being two separate but related paradigms. They each fit on a continuum from less to more. And they have direct influence on each other. Said another way, the level of a skill or ability directly influences how much support should be provided. And how much support is provided will directly affect skill development. So what is the optimal amount of support? And how do we know how to adjust the amount of support we give? Since I’m a speech-language pathologist it is most relevant for me to give an example regarding speech development. First of all we’ll look at the Skill paradigm. This example reflects how much ability or skill the child has producing a specific phoneme (speech sound). As the above illustration shows, the child moves from the most basic level of ability, which is production of the sound in isolation (by itself). Once the child can accurately produce the sound in isolation, we move to saying the sound in a word, then to saying the sound in a word in a sentence. And finally, the child uses the sound in a word, in a sentence during spontaneous speech (in a real life context). There are often substeps to the above Skill paradigm illustration which your child’s SLP will be aware of and guide you through. Some examples of substeps are closer and closer approximations to saying the sound in isolation, saying the sound in syllables, saying the sound in one syllable words before multisyllabic words, saying the sound in different positions in words, etc. Moving from producing the sound in isolation to using the sound in words in sentences in spontaneous speech can take months or even years depending on the child and the sound. Each step is a significant achievement and needs to be celebrated. Practice eliciting the sound in isolation, and at the word and sentence level are often initially done during “structured practice time”. This is because it takes a lot of focus to learn a new skill. During structured practice time, we can offer time to focus on speech work, without distractions, or time pressure. But eventually, and ultimately, we have to be intentional about making sure the new sound is carried over to real life speaking situations. So now let’s talk about the Support paradigm. The Support paradigm shows how much support we need to give a child during skill development. It’s important that the goals we choose are at exactly the right level. A goal that’s too easy means the child already has that skill. A goal that’s too hard means that even with support the child has a very low rate of correct responses when trying to achieve the skill. Let’s assume our speech sound goal is at the right level. This is what the Support paradigm looks like: The Support paradigm moves from the child needing full support to needing no support. Full support is when numerous supports or cueing methods are used, for example, to elicit a sound. Full support can mean hearing the adult model the sound, seeing the Sign Sound for the sound, watching how the mouth moves, producing the sound with the SLP while looking in a mirror together, getting verbal cueing (such as “smile” or “keep your lips together”), etc. For moderate support the child still needs several cueing methods to achieve success. For minimal support the child needs only one or two cues, or needs cues only intermittently to achieve success. And finally, Independence means the child is independent in producing the sound without any cueing required. It is important to explicitly reduce and then withdraw support to increase independence. Independence with a skill is our ultimate success.

One of the most important concepts to embrace is how the Skill and Support paradigms interact. As you move up the Skill continuum, each new level may initially require more support, and move through the Support continuum. For example, once a child learns to say a certain sound such as /m/ in words, it can be a significant hurdle to then ask the child to use that word in a phrase or sentence. Instead of just having to concentrate on saying the sound in a single word, the child now has to think of all the sounds in all the words in the sentence, get the words in order, and figure out the meaning. These “distractions” make it harder to concentrate on articulation of the target sound in the word. But fortunately, we can provide more support at this new Skill level, so the child has a greater likelihood of success. The amount of support we provide is directly linked to how much support the child needs. Success is important. We want our children with Down syndrome to practice the right way. Each time the child says /m/ incorrectly, they are cementing a misarticulation in their memory. Each time the child says /m/ correctly, they are cementing correct production of the sound in their memory, which makes it easier and more likely to produce the correct sound next time. Success builds upon success. It all starts with very carefully chosen goals, and an in depth understanding of how the Skill and Support paradigms interact to enhance learning, independence, and success :) Speech is complex. When we look into the features of speaking we realize how much information we need to know, and how many precise coordinated movements we need to make when we speak. What’s especially amazing is that many of us learn to speak seamlessly with seemingly little effort.

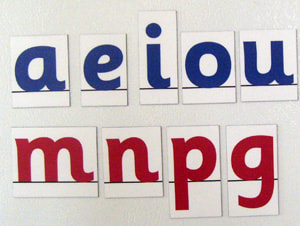

For those of us who have children who are working to develop their speech, or for those of us who work with children with speech delay, it can be helpful to dive into specifics. In this blog post I will be explaining the properties of phonemes. A phoneme is a speech sound. As a Speech-Language Pathologist, I consider several important phoneme properties when I’m analyzing a child’s speech. Here are the top three: place of articulation, manner of articulation, and voicing. Place of articulation can be taken quite literally. It means where in the mouth the phoneme is made. So is the sound made with the lips? Is the sound made primarily with the tongue? And if so, where in the mouth is the tongue touching, or closest to? Here is a list of phonemes according to place of articulation with examples. It can be helpful to say each sound (no letter names) and be aware of where the sound is being made. Consonant sounds are classified by the following place of articulation. Bilabial – sound made with the 2 lips - /b, p, m/ Labiodental – sound made with the lower lip and upper teeth - /f, v/ Alveolar – sound made with the tongue touching or closest to the alveolar ridge (the bump behind the top teeth) - /t, d, s, z, n/ Palatal – sound made with the tongue closest to the hard palate - /sh, ge/ Velar – sound made with the tongue closest to the soft palate or velum - /k, g, ng/ Manner of articulation means how the sound is made. The most basic classification of manner of articulation is whether the sound is a plosive or a continuant sound. A plosive sound is made when the articulators come together and stop the flow of air out of the mouth, and then burst open, or explode to make the sound. Some examples of plosive sounds are /p, b, t, d, k, g/. You cannot hold a plosive sound. Once the sound bursts forth, it is gone. Alternatively, a continuant phoneme is made with the articulators narrowed, but not completely closed. So a stream of air can continue to produce the sound as long as there is outgoing breath. Some examples of continuant sounds are all the vowels, and many consonants such as /s, z, f, v,sh/. Voicing refers to whether or not the vocal folds are vibrating during the production of a phoneme. Voiceless consonants are made with the vocal folds open, allowing unobstructed passage of air from the lungs and through the layrnx. An example of a voiceless sound is /s/. Voiced sounds are made with the vocal folds vibrating very rapidly, which produces a source of sound at the level of the larynx (or voicebox). An example of a voiced sound is /z/. You can test this out yourself by gently placing your hand over your larynx while saying /s/ and then /z/, and noticing the lack of vibration for /s/ and the vibration for /z/. The interesting thing about voicing is that only some of the consonants are voiceless. Many of the consonants and all of the vowels are voiced. Also, every voiceless consonant has a matching voiced counterpart. In voiceless-voiced consonant pairs, the same thing is happening in the mouth; the sound only changes by either turning on or off the vocal fold vibration. Thinking of /s/ and /z/ - they are made the same way in the mouth. But /s/ has unobstructed passage of air through the larynx (voiceless), whereas /z/ is made with the vocal folds vibrating. Combining classifications Individual phonemes are classified according to all of the above characteristics or features. So we would say /b/ is a voiced bilabial plosive. We would say /s/ is a voiceless alveolar continuant. SLP analysis When a SLP analyzes a child’s speech, he/she looks at all the above properties, and notes how the child says each sound. Is the sound omitted completely, or only in certain positions in words? Is one sound substituted for another sound? If so, what kind of substitutions does the child make? For example, are all the voiceless consonants voiced? It is helpful for parents and educators to understand these basics of speech sound properties to help you understand the speech sound goals your SLP has chosen. You will also be better equipped to understand what your SLP has asked you to focus on during speech sound practice. As a mother, and an SLP with a passion to see children with Down syndrome succeed, I focus heavily on speech sounds. The speech sound system is often a confusing puzzle to children with Down syndrome. Hearing, distinguishing, and producing speech sounds can be challenging. Identifying individual sounds in words, and matching them with letters is a foundational literacy skill, that is also challenging. However, the way we approach instruction about speech sounds can make a huge difference not only for articulation, but for reading and spelling success.

I have long advocated the importance of targeted, intensive practice to develop our children's articulation accuracy. And in tandem, I have long advocated focusing on letter SOUNDS, and explicitly not teaching letter names to beginning readers. I have just come across two blog posts that explain the importance of teaching letter sounds, and not letter names. I'll put links to both blog posts here: https://theliteracyblog.com/.../sounds-or-letter-names.../ https://theliteracyblog.com/.../advocating-the-teaching.../ I welcome your comments, and hearing about your experiences. Once children are verbal and able to remember words and numbers, I make a point of teaching them to clearly articulate their name, phone number, and address. This of course relies on their memory. And it requires the child to use slow, deliberate speech, with pauses between words. This gives the listener the best chance of understanding what is being said.

I recently read an article that highlighted a main reason why we teach children to memorize their basic information. You can read it here (I recommend reading the story, not the video): https://globalnews.ca/news/6017343/antony-robart-blog-lost-son/?utm_source=GlobalHalifax&utm_medium=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR0J9Bz_wq4i0gHkfoMf5_aOGFuzpJXJunbCz2ij42xCeolnWXBeGbIShxk Let's strive for a school system, where from the top down, administrators, and educators see their role as including being advocates for all students, including students with disabilities. In this article, Greta Harrison makes important statements, " I believe parents of children with disabilities receive much more “bad news” from teachers than good news.....I have been thinking about how different each school and school system would be if every educator had a positive attitude — if every educator truly felt they were each child’s advocate. "

https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/why-teachers-become-advocates-kids-210455400.html In this video, Jill explains the best way to teach your child the meaning of spoken words.

Why teaching letter names may impede your child's learning. Fortunately, there is a better solution. Jill explains. By Jill Hicks, M.Sc., Speech-Language Pathologist By Jill Hicks Sometimes students with different learning abilities are assigned to a "Life Skills" program. The problem isn't with learning life skills. Life skills are important. The problem is deciding students with Down syndrome should not be included. That they are incapable of benefiting from academic instruction. Click on the colored "Read More" to continue.

|

For a powerful resource to help your child speak

AuthorJill Hicks is the mother of a child with Down syndrome and a speech-language pathologist. Her passion is to empower others to help people with Down syndrome. WhArticles

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed